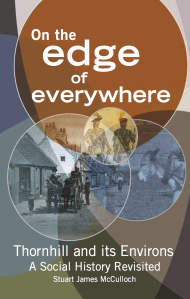

According to local historian and author, Stuart McCulloch, Thornhill is

“on the edge of everywhere” and its inhabitants were involved in many of the key events in Scottish history.

Many thanks to Stuart for the description of Thornhill’s history below.

Proceeds from the sale of Stuart’s book go to Thornhill Development Trust and are used for the benefit of the community. The book is available for £10 from the Village Store, Thornhill or email secretary@thornhillstirling.org

Behind the sleepy facade of the white and grey stone houses of the village lies a tale; in fact, very many tales. This small village was once considered (erroneously) to be almost at the geographical centre of Scotland but it would be more accurate to look at Thornhill as on the edge; between mountain and moss land, between Highland and Lowland, between Pict and Scot, between Highland Gael and Lowlander and between industrialisation and traditional life. Life on the edge is rarely dull, so this small part of Scotland was able to bestow its hidden tales and secrets; and there were plenty of them. This peaceful village reflects, in microcosm, much of Scotland’s turbulent past.

Prehistoric hillforts and ‘duns’ surround the area and from a later date mysterious ‘brochs’ are also to be found, perhaps tied in with the Roman invasions or the warlike period following their withdrawal. Locally, ‘at the edge’, this time between the Strathclyde Britons and the Pictish kingdoms to the north and east. The local area, Menteith, remained ‘at the crossroads’ for many hundreds of years as Picts, Gaels, Britons, Angles and Vikings battled for local supremacy, all leaving their legacy. Certainly by 1100 the Dalriada Scots had prevailed and their language, Scots Gaelic, was to become established as the overriding spoken language of the area.

Up until very recent times much of the land was divided into sizeable estates and they were owned by a relatively small number of ‘lairds’. These lairds, notably the Stewart Earls of Menteith, the Drummonds, The Grahams, the Muschets, the Napiers, the Dogs and the Norries dominated local human activity, and what a colourful bunch they were!

Sir John Menteith of Ruskie, born sometime about 1260, has been called, (perhaps unfairly), ‘Scotland’s greatest traitor’ for his role in the capture of Sir William Wallace.

The Drummonds first appeared around 1330 and were active in a feud against the Menteiths and later became the leading aristocratic family of the area. Blair Drummond was so named around 1684 and the Drummond Estates have formed a significant part of the local landscape right into recent times.

The Norman Muschets first arrived in Menteith in 1189 and exploded on the national scene when Lady Annabella Muschet married King Robert III, with their youngest son becoming James I of Scotland.

The Grahams and Napiers became involved in the Civil Wars of the mid-17th century and were strong supporters of the Kings faction. The support for the Stewart Kings continued into the late 17th century when William Graham of Boquhapple the right hand man of Viscount Dundee, was sentenced to death for his role at the battle of Killiecrankie. The Napiers were financially ruined for their royalist support and Archibald Napier (great grandson of John Napier, the inventor of Logarithms) inherited the lands of Boquhapple.

The Nory family has established the small hamlet of Norriestoun to the east of Boquhapple. Although it was an ecclesiastical centre it had no economic or trading function, so in 1695 Archibald Napier persuaded the Scots Parliament to authorise the holding of

… four fayrs settled and established yearly at the Toun of King’s Balquhaple in the parochin of Kincardine.

He also obtained permission to have a weekly market on Thursday with four larger fairs each year, each one to last 8 days. All he now needed were some people to make his markets and fairs a financial success so Archibald began to grant feus of land on the gently rising thorn covered ridge which ran westwards from his eastern boundary with Norrieston.

Thornhill was born.

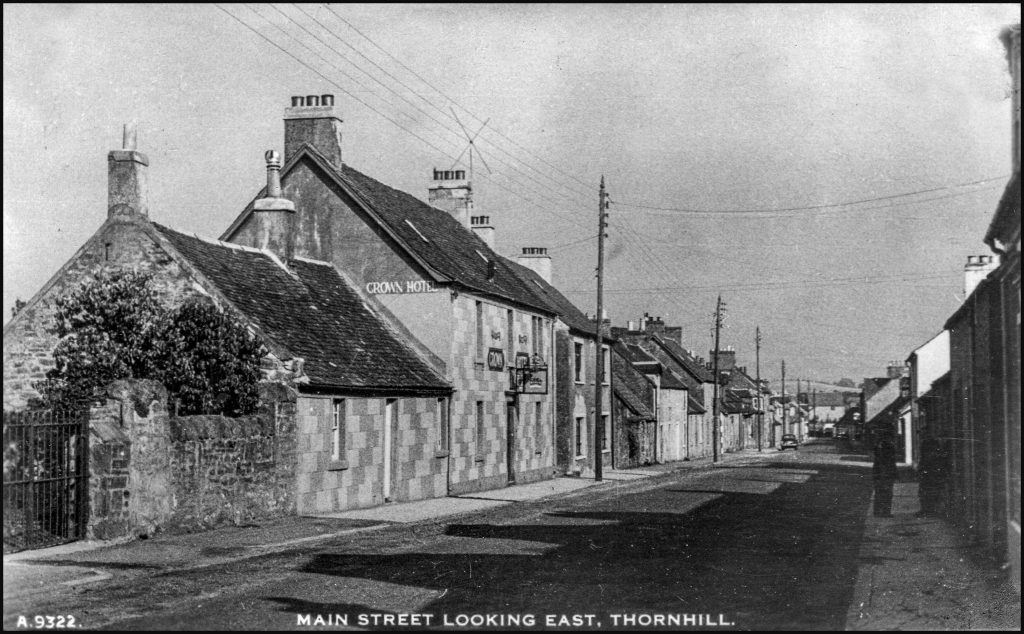

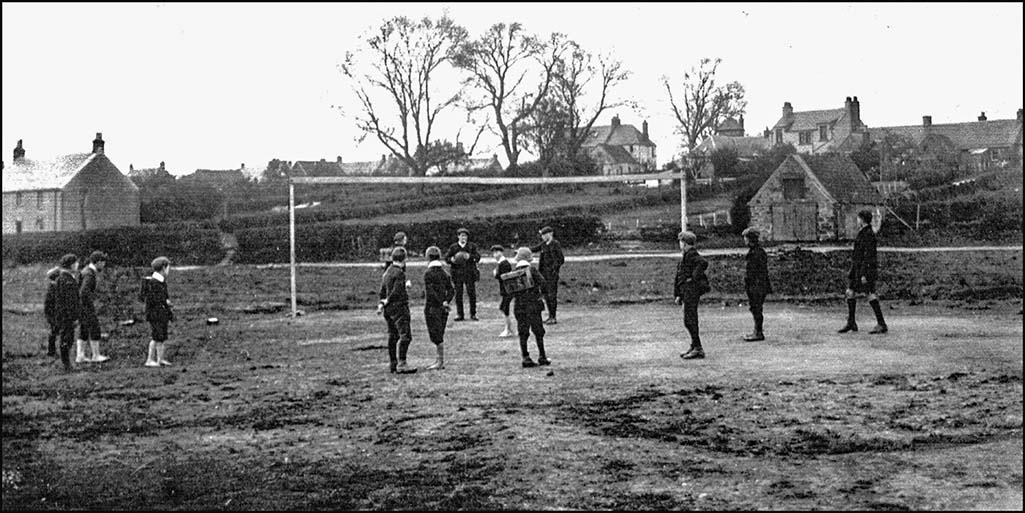

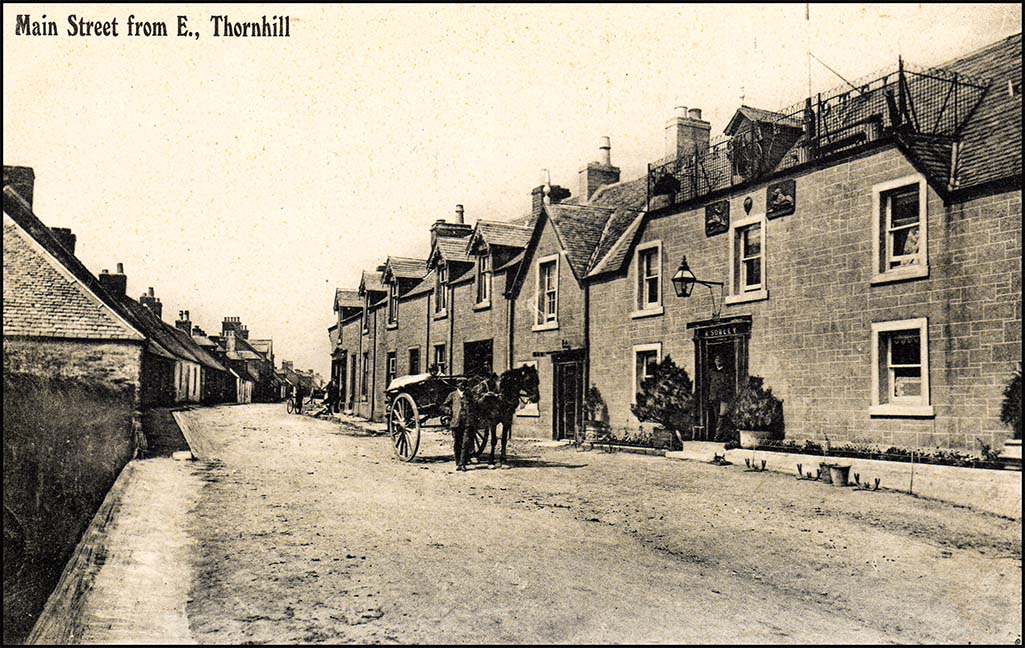

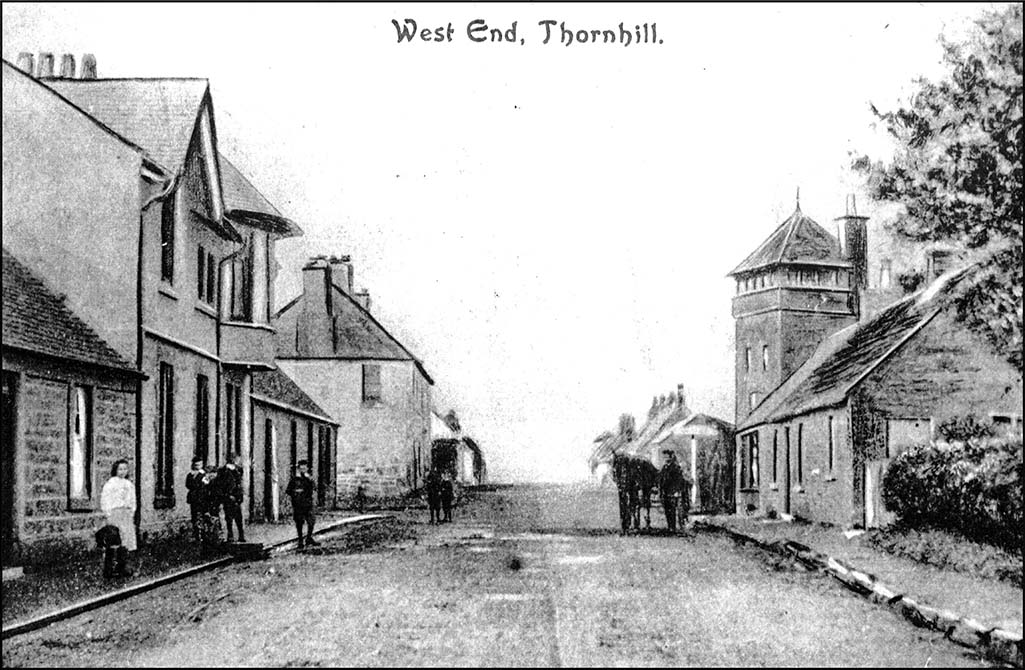

Thornhill’s original planned layout, little changed today, is of a main street broadly following a cruciform pattern, with a dominant Main Street and a Cross Roads. Initially the village houses were little more than huts, with holes for windows but 1790 all the houses in the village had glazed windows. The feus behind the houses gave enough space for growing potatoes and other crops and the keeping of a limited number of animals. Common grazing was on the North and South Commons. Some of the barns and byres can still be seen and the Common lands are still in extant. The North Common maintained its original function as a common grazing area well into the 20th century and is now valued as an area of open space for the villagers.

The early industry was Whisky distilling. It was said of the people that:

Most people are religious, sober, industrious and frugal but several are intemperant…because of the effects of distilling local whisky.

By 1861 the population of Thornhill was about 621 with most people being employed in farming, but the agriculture was changing. The developments on the surrounding moss areas (by 1865 over 10,000 acres of the Carse had been cleared, leaving behind just the now-protected Flanders Moss) attracted world-wide interest and were a part of a general but dramatic change in which fields were enclosed, new techniques were adopted and marginal land was brought into cultivation. There were inevitably winners and losers and many tenants were dispossessed.

Access to the important river crossings at Frew and later the military road to Inversnaid had ensured that Thornhill was not too isolated, but in the 1840s and 1850s there was a frenzy of railway building. It was considered essential that if a settlement was to grow it needed railway connections. But no line went to Thornhill.

Thornhill is unknown to many because of its difficult and poor access… If you have not been there I would say go at once. As a health resort Thornhill is foremost…and all the people require to make their village a busy one in winter and well frequented in summer is a railway.

Once more Thornhill seemed to be ‘on the edge’. However it also meant that urban growth was limited and today the village is much admired for its retention of its design plan. Its relative inaccessibility meant that community spirit became remarkably strong and a very high level of village social activity with dances, socials and community meetings of all types, was a notable and important part of village life. Of course there were some disputes, but overwhelmingly evidence suggests that the villagers were a happy and friendly society. That is not to say that the area did not face huge challenges. Poverty and squalor were never far away and in World War almost 1/3 of the total number of males of the village were killed or injured.

Today Thornhill could still be regarded as ‘on the edge’ although not remote. Its distance from the central belt now makes it possible for residents to follow a commuter lifestyle with some working in Stirling or further afield. Nevertheless, it retains its core of agricultural activity and its country lifestyle. Thornhill lies just outside the Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park but the relative lack of change from the initial village foundation in 1696 makes Thornhill, although not unique, very significantly valued. Its historic and heritage appeal is now recognised and the designation of parts of Thornhill as a conservation area underlines this. The multiplicity of local clubs and activities remain a local feature and the on-line presence, especially through the work of the Thornhill Community Trust, means that interest in the history and heritage of the village and its surroundings remain robust.

The active and friendly environment means that a local newspaper description of the village from over 100 years ago, as ‘the pleasantest of pleasant villages’ still applies today.